Will the Pandemic Revive Hands-on Projects?

This author believes (or hopes anyway…) it will.

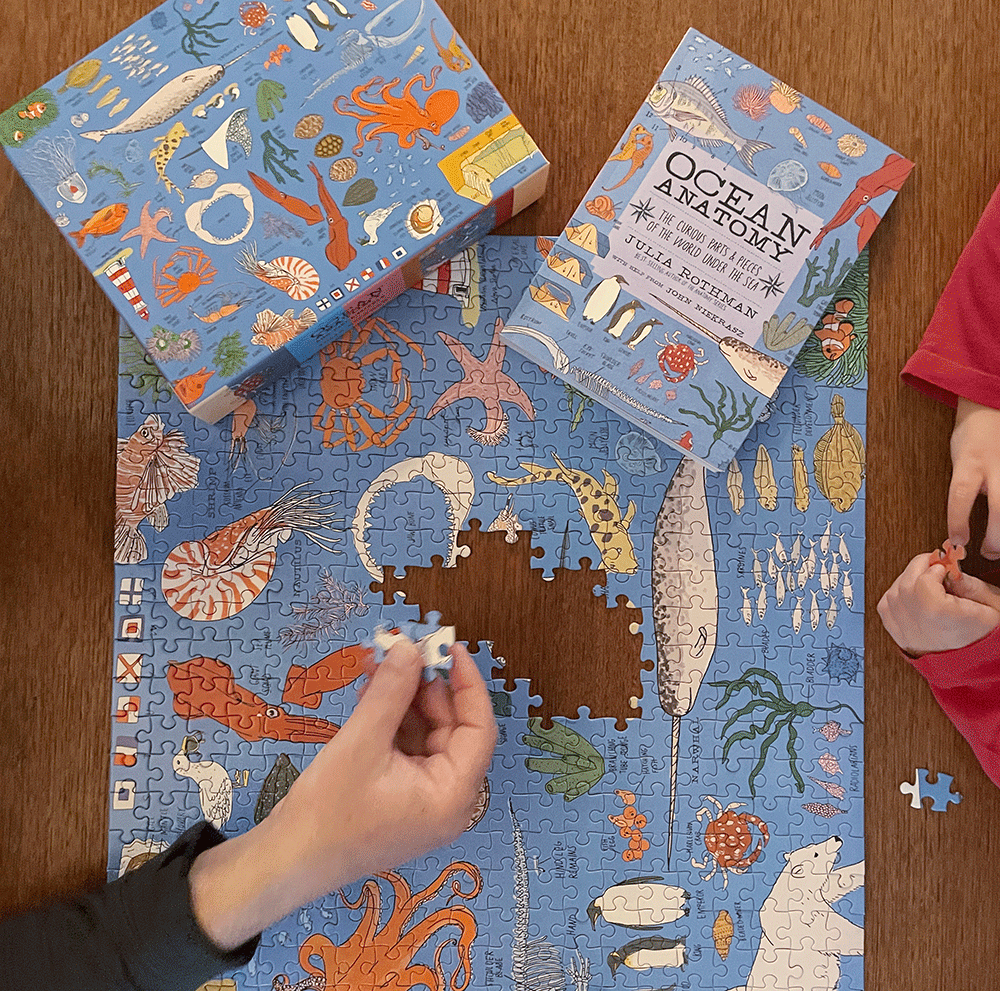

Stop me if you see a pattern here. My wife, having never previously demonstrated an interest in puzzles, has recently become a jigsaw junkie, burning through 1,000-piece projects every two weeks. Many of her friends are doing the same. Harry Potter star Daniel Ratcliff says he has become similarly obsessed with assembling Lego sets. Meanwhile, everyone on Instagram, it seems, is showing off artfully shaped loaves of home-baked bread.

Yes, all of these are diversions that help take our minds off the unfolding global pandemic and pass the time when we are stuck at home, but there’s something about the specific nature of these activities that I find revealing, a shared characteristic that offers a clue into what many of us appear to be needing more of in life.

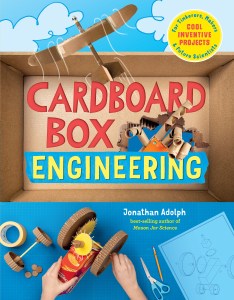

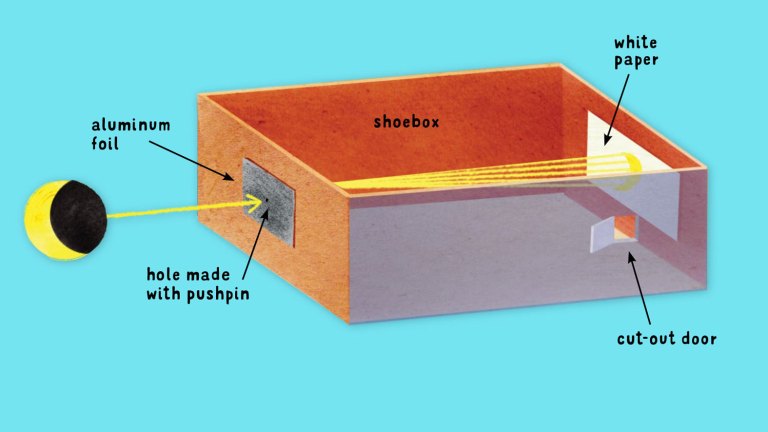

All of these pandemic pursuits are hands-on structural activities. That is, they require people to manipulate physical objects to solve challenges in three dimensions. In writing my new book, Cardboard Box Engineering, I spent months developing toys, games, and other intricate contraptions from cardboard, so I certainly understand the satisfaction that comes with hands-on structural work. But I still had to wonder: Why has this time brought out what seems to be the repressed engineer in so many of us?

Here’s one answer. In one of my first jobs out of college, I worked for a company that tested aptitudes—the inborn predispositions we all have that determine how quickly or easily we learn certain skills. The testing company had found, over many years of evaluating and counseling clients, that people are most satisfied in their careers when their work allows them to use their strongest aptitudes.

A person who is full of ideas, say, would feel most fulfilled working in a creative field. A person with a high aptitude for inductive reasoning, who quickly made connections between pieces of information, would be happiest in a field that required solving problems, and so on.

Notably, the company found, if people are not working in a field that lets them express their aptitudes, they will often seek out pursuits or hobbies that do. You may see where I am going with this.

This period of pandemic seclusion, by providing time and opportunity for our deeper needs to surface, has revealed for many of us a desire to manipulate physical objects and solve structural problems. And because in today’s screen-based remote-working world, few of us have the opportunity to do that in our jobs, we are turning instead to hobbies.

Hence the unprecedented surge in the sale of jigsaw puzzles and Lego sets and the bare shelves in the grocery store where the baking flour used to be.

As an aspiring old codger who remembers life before screens, this heartens me. Structural problem-solving—the desire to transform the physical world, to fashion useful or beautiful things using our hands and imaginations—is an impulse as old as humanity, but one that often gets passed over today in favor of more captivating technological distractions.

This loss is particularly troubling for structurally minded kids, who not so long ago might have spent their free time making models, or whittling, or building tree forts—pursuits that today are often replaced by playing video games or tapping on phone screens. (Granted, computer programming requires structural thinking, as does playing many video games. But the end result is not a physical thing you can hold in your hands.)

Understanding this trend is vital to all of us because tomorrow’s scientists, engineers, and designers need to develop their structural skills if they are to solve humanity’s future problems. Educators understand this and have responded by underscoring the importance of introducing kids to science, technology, engineering, and math, the so-called STEM fields.

But if we want to recruit and truly engage future problem solvers, we need to help them experience STEM activities for the pleasures they can bring. We need to let them feel the natural gratification that comes from using their structural aptitudes to creatively shape the world. It can be as simple as letting them tinker with a broken appliance, bake their own apple pie, or (shameless self-promotion alert) build a glider from cardboard and hot glue.

As I suggest in my book, the point of this is not just to learn how to build with cardboard (or pie dough), but to learn how to build with any material, “because the process of engineering is the same no matter what material you are tinkering with.”

We humans will have a sustainable future only if those with exceptional aptitudes are encouraged to use them to their full potential. The good news, as pandemic seclusion has shown so many of us, is that using your aptitudes is deeply satisfying. It seems natural and right. I’m hoping that making the projects in my book will allow the next generation of inventors to experience that feeling of creative achievement and persuade them to seek it out when it comes time to choose a career.

Because, soon enough, the world will be facing another pandemic—or something even more challenging—and we will need all the skills they have to offer.