The Power of Mulch to Help Fight Drought

It doesn’t matter how much rain you get if most of it never enters your soil. Mulch is one powerful measure you can take to make soil moisture-efficient.

On May 5, 2015, a tornado hit my hometown and wrought terrible destruction. It destroyed the home of a dear neighbor and dumped up to 7 inches of rain in just a few minutes, causing massive flooding in the area. My creek-bottom pasture was under 3 feet of water, my fences were washed out, and my cattle went on a three-day walkabout.

Very few soils are in a condition to absorb rainfall that intense. My son and I were tornado chasing, and he had his camera pointed out the window at the funnel cloud to the east. As I passed our farm I saw something that made me hit the brakes. All along our drive that afternoon the road ditches were overflowing — until we came to the ditch at the bottom end of my farm, which was empty. According to the nearest intact rain gauge, we had received 4.5 inches of rain in about 20 minutes, and the entire quantity soaked into my field. All my neighbors are excellent farmers, and I am not trying to portray them as bad examples at all. But the rain was pouring off their fields in small gullies several feet across, and every drop that fell on my field stayed on my field.

It was a small ray of personal sunshine in the middle of a huge tragedy. It told me that what I had been trying to accomplish with my soil management had worked. It really doesn’t matter how much rain you get if most of it runs off and never enters your soil. Therefore, the very first step in being more moisture-efficient is to make sure the rainfall you do receive actually goes into your soil.

How Water Travels Through Soil

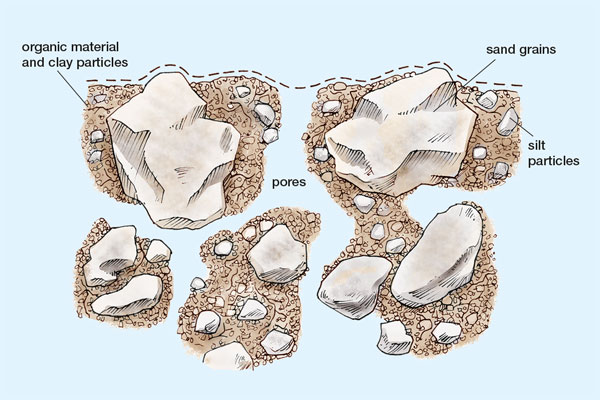

There are two major forces acting on water in soil: 1) gravity; and 2) the attraction of water to the surfaces of soil particles. The more surface area a soil has, the more attractive force it has for water.

The pull that soil particles have for water is far stronger than gravity. This is evidenced by the fact that a column of soil placed in water sucks the water up into the column against gravity, like a straw. However, this attractive force extends only a microscopic distance from the soil particle. This means that water even a few millimeters away from direct contact with a soil particle moves under the influence of gravity.

By contrast, water in close contact with soil clings tightly to the soil particle until it is coated with more water than it can hold, a condition we call saturation. If soil particles are packed together tightly, water does not move down until each successive layer becomes saturated. The key to getting water into the soil, then, is to have large pore spaces (macropores) open to the soil surface so that water can enter without actually touching soil particles.

Mulch

Perhaps no other practice improves water movement into the soil surface more effectively than creating and maintaining a mulch layer. The primary benefit of a mulch layer is not that it slows the velocity of overland water flow, as is often assumed (though that is important); rather, it is that mulch absorbs the energy of falling raindrops and thereby prevents raindrop impact from destroying soil aggregates. If the aggregates remain intact, the water goes into the soil through the intact large pore spaces, and there is no runoff to slow down.

Keeping the Residue We Already Have

So how do we create a mulch? The first and most obvious way is simply to avoid destroying or removing the mulch we have as a byproduct of our current land management, such as crop residue or the stubble of pasture grass.

Keep Plant Residues in the Field

Potassium deficiency predisposes plants to stalk rots, which are fungal diseases that infect the lower stalks. Once the lower stalk is infected, it not only makes it difficult for the plant to take up water and nutrients, resulting in reduced yield, but the structural integrity of the stalk is compromised as well, and the plants begin to lodge (fall over) and become difficult to harvest. When crop residue is harvested year after year, the most easily available potassium ions are largely removed from the surfaces of soil colloids and transported away in bales of stalks and straw.

I have seen formerly rich soils become progressively impoverished by too much removal of crop residue. On top of that there is the issue of soil erosion. Removing the protective layer of natural mulch leaves the soil more vulnerable to erosion.

Avoid Overgrazing

Similar to the removal of crop residue on cropland is the overgrazing of pasture lands. It is critical to leave a minimal amount of grass residue on the soil surface to promote water infiltration. If there is any bare dirt showing (other than in high-traffic areas such as gateways), there has been too much forage removal.

Not only does bare, exposed soil reduce infiltration, but it also means that there is sunlight not being captured by green leaves, and not contributing to pasture productivity.

No-till Covercrop Mulch

On cropland and gardens, we can add to the amount of mulch left by crop residue by growing cover crops in between cash crops. A cover-crop mulch can dramatically improve infiltration. Cover crops can be managed to provide multiple benefits (including valuable forage for animals during drought), but perhaps the most beneficial is the addition of surface mulch.

As with all mulches, no-till is essential to maintaining this benefit. Old, decayed root channels act as passageways for water into the soil; even a little tillage can damage the continuous open channel from the soil surface into the soil. The best value by far for improved water infiltration comes from creating additional root channels selected for the purpose. For maximum benefit, blend fibrous-rooted cover crops with deep taprooted cover crops. Fibrous-rooted cover crops include annual ryegrass, rye, barley, buckwheat, and phacelia. Taprooted cover crops include sweetclover, brassicas (such as turnip and radish), okra, and sunflower.

A word to the wise: Cover crops typically don’t grow any better during a drought than cash crops do. Don’t wait until the next drought to plant cover crops. Start now and build that desirable organic layer during the good years.

Bringing Mulch In

Of course, we can also simply import organic materials for mulch and apply them to our soil surface. This is obviously much more economical on a garden than it is on fields or pastures, depending on the cost of the material and the cost of hauling and spreading. By all means, if organic mulch can be found at reasonable cost, utilize it.

Be aware that some organic materials that are very low in protein content (like sawdust) can tie up nitrogen upon decay. Soil microbes need nitrogen in the ratio of 1 part nitrogen to about 28 parts of carbon. If the residue is too low in nitrogen, microbes will rob the soil of nitrogen to balance their needs. Wood chips decay much more slowly than sawdust because they have less exposed surface area, and they are much less likely to tie up nitrogen. Some materials, like black walnut and red cedar products, can have a toxic effect on some crops. Always inform yourself about what you apply to your land. In terms of quantity, the general rule is that more organic matter on your soil is better than less.