6 Things to Know about Bourbon

This distinctly American spirit has been shaped by everything from France and fire to wood and weather.

It is likely that we will never know with certainty the first person to distill corn into whiskey, and why should we? We don’t know who first distilled barley into whiskey in Ireland or Scotland, either. Here are a few things we do know (and a theory on the origins of aging, thrown in for good measure).

Bourbon By the Rules

To be bourbon, whiskey must be (1) made and aged in the U.S., (2) made from a mash that is at least 51% corn, (3) distilled to a proof no higher than 159 (79.5 percent ABV), (4) aged in new charred oak barrels and put into the barrel at no more than 125 proof (“entry proof”), and (5) bottled at no less than 80 proof, with no coloring or flavoring added. Although most of it is, regulations do not require that bourbon be made in Kentucky.

Cypress and Steel

Bourbon is fermented almost entirely in column stills that were traditionally made from cypress wood. When cypress was just no longer available in the quantities needed to build the big tanks, master distillers determined — happily — that steel tanks would make the same whiskey. Some distillers still use cypress — that’s their tradition.

As the French Do?

The most common explanation you’ll hear on why oak barrels used for aging bourbon were charred is that it was done so they could be reused; the charring, the explanation goes, would take the smell of the previous contents out of the wood. There is evidence, though, that the barrels were deliberately charred to affect the flavor of the whiskey, emulating the aging process used for French brandy and cognac. The popularity of these two imports in New Orleans may have been what led Kentucky whiskey makers to adopt the practice.

The Barrel’s the Thing

Unlike Scotch, very little of bourbon’s flavor and character comes from the size and shape of the still. Instead, bourbon gets at least 50 percent of its flavor from the barrel. The longer the bourbon spends in the barrel, the more oak flavor it has. Charring begins the process of breaking down lignin — a natural polymer in the wood — and, as alcohol continues the breakdown, it creates flavor compounds that give the whiskey familiar characteristics, such as vanillin, the source of bourbon’s creamy vanilla notes.

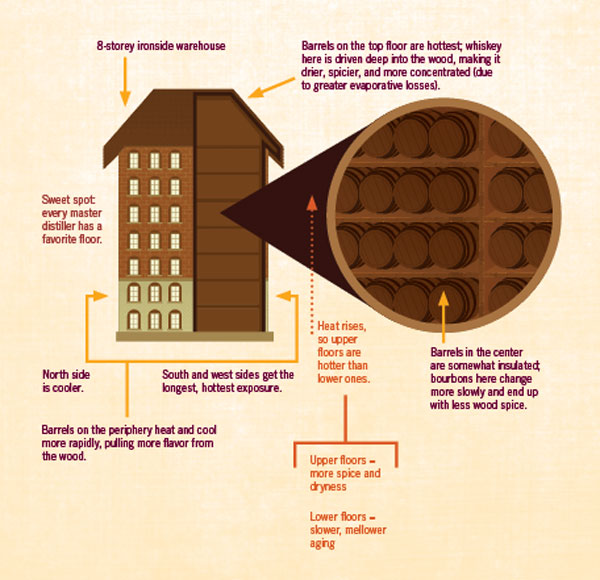

The Higher the Heat, the Bigger the Spice

Equally important as the barrel to bourbon’s flavor is how and where the bourbon is stored.

Berm, Baby, Berm

In 1996, Heaven Hill’s Bardstown facility suffered a disastrous fire. Seven warehouses full of bourbon were lost, and an 18-inch deep river of burning whiskey flowed down the hill and destroyed their facility. As a result, whiskey warehouses are now required, by regulation, to have sprinkler systems, multiple escape routes, and be surrounded by a berm to contain burning whiskey.

TEXT EXCERPTED AND ADAPTED FROM TASTING WHISKEY © 2014 BY LEWIS M. BRYSON III. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Pour a stiff drink and crack open this comprehensive guide to everything there is to know about the world’s greatest whiskeys. Exploring the traditions behind bourbon, Scotch, Irish, and even Japanese whiskey, you’ll discover how unique flavors are created through variations of ingredients and different distilling techniques. With advice on how to collect, age, and serve whiskey, as well as suggestions for proven food pairings, you’ll be inspired to share your knowledge and invite your friends over for a delicious whiskey tasting party.

Related Books

Articles of Interest

Featured Content

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use