What Is Single-Origin Chocolate?

As the bean-to-bar movement grows, so does demand for chocolate that celebrates the origins and flavor profiles of the cocoa from which it is made.

We all know what chocolate tastes like. It tastes like chocolate, right? But if you stop and think about it, how would you describe that flavor? Maybe sweet and roasted, or nutty and earthy? What about fruity, even when there isn’t any fruit in it? The first time I tried a bar made with cocoa from Madagascar, I almost fell over: it tasted like raspberries! It turns out that chocolate can taste like many things. Most of all, it tastes like the place it came from.

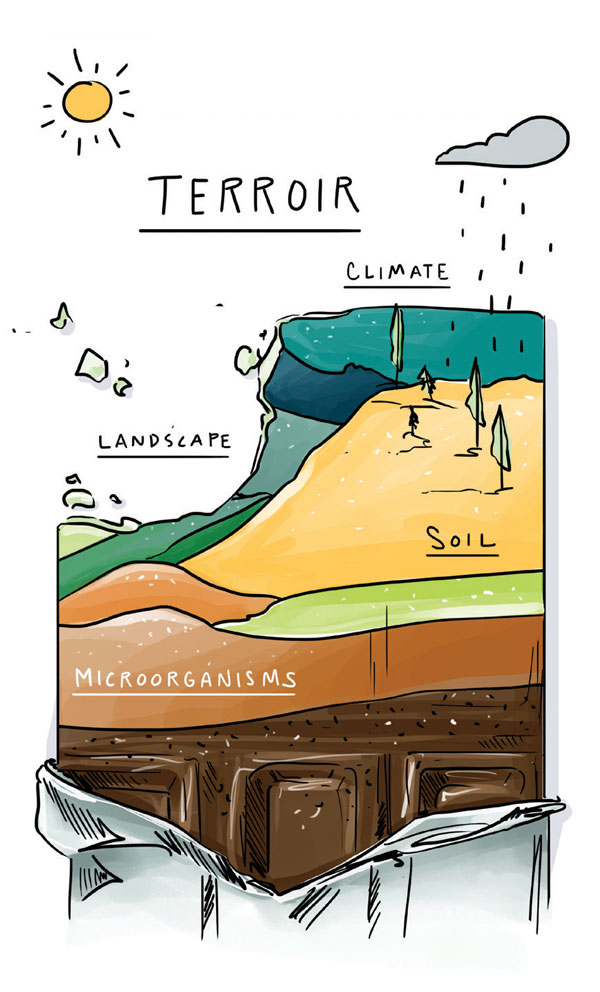

Like with wine and its grapes, chocolate’s taste is partially determined by the environment in which the cacao trees grow. Cocoa beans from different regions have their own distinctive flavors. For example, as I discovered early on, cocoa from Madagascar often tastes fruity, whereas cocoa from Venezuela has a nuttier profile. In the snooty food world, this is called terroir. It means the taste of the beans is affected by the soil, landscape, and environment in which they’re grown. In fact, those fruity notes we often taste in chocolate are the direct result of terroir. (By the way, terroir affects not only wine and chocolate but also coffee, cheese, tobacco, and even maple syrup, among other foods.)

Most of us don’t usually put chocolate in the same category as wine or coffee, though, and we expect every chocolate bar to taste the same. That’s because over the past hundred years or so, chocolate-making companies have worked hard to standardize the taste, using a blend of beans and adding a ton of other ingredients to mask any bitterness or distinctive flavors (some companies like Hershey and Mars even have proprietary blends!). What most of us know as chocolate is really just sugar and vanilla.

That’s where bean-to-bar makers come in. Bean to bar technically means that the maker oversees the entire process, from buying beans to roasting them to grinding them and turning them into chocolate. But in practice this means that people spend a lot of time and care creating a unique chocolate. Instead of creating a uniform product, they strive to bring out the different flavors of each bean to maximize taste and make something special. Most of them create bars using beans from one country in order to concentrate on the terroir of that particular bean (some even use beans from just one farm!). This kind of chocolate is called single origin, a term you might already know if you’re a coffee connoisseur or a wine aficionado. French company Valrhona pioneered the focus on origins in the 1990s. Not all bean-to-bar chocolate is single origin, but many makers specialize in single-origin bars because they want to highlight the inherent flavors in the cocoa. (How do they highlight those flavors? Through the bean-to-bar production process.)

Many makers will designate not only the country of origin but also a specific area within that country. For example, in Venezuela, you’ll find amazing beans from the Ocumare region as well as the Maracaibo region. When you see that kind of detail on the label, it often means makers have personally visited that area, worked with farmers, and acquired the beans themselves.

Some people take this idea even further and make single-estate chocolate. That means the beans come from not just one particular location but one particular farm within that location. This almost always means the maker has spent extensive time at the farm (and sometimes, in the case of bigger companies like Valrhona and even tiny ones like Lonohana, it means they actually own the farm!). They’ll be able to tell you how one harvest tastes different from another and why, and they’ll be able to give you tons of details about the farmers’ lives and how they worked with and processed the beans. The more they dial down to a specific country, area, and farm, the more they’re able to control the way the chocolate tastes. Of course, the single-estate designation doesn’t guarantee that the resulting chocolate will taste good, but it’s often an indicator. When you see a single-estate chocolate, know that you’re most likely eating something special.

The terms single origin and even single estate don’t mean that the chocolate is being made in the country where the beans are sourced. Most makers buy beans from farmers in other countries and ship them back to their factories in the United States or Europe. There are exceptions, of course: Pacari makes fantastic raw chocolate in Ecuador, and Marou makes amazing bars in Vietnam.

Although the term single-origin chocolate is new, people have been categorizing the sweet stuff by location for hundreds of years. The Aztecs organized their supplies of cocoa beans according to where they were grown, and in the late 1700s, Peruvians even considered creating official fixed prices for cocoa beans based on origin and quality. With the industrial era, the concept of classifying cocoa this way faded — perhaps, as I mentioned above, because at first bigger companies simply wanted to keep their recipes secret, but over time some began blending lower-quality beans from many different locations and overroasting them to disguise their acidity and bitterness and create a uniform product.

Keep in mind that not all good chocolate is single origin, and not all single-origin chocolate is necessarily good. Some people overlook this, as Alan McClure of Patric Chocolate knows all too well. When he first started making a blended bar in 2010 (one of the first craft blends in the country!), some wholesale customers “not only wouldn’t order some of the blend and flavored bars but didn’t even want a sample of them to consider, and all because they were not single origin,” he recalled recently. “[Blends were] a risky thing to do.” Yet blends of high-quality chocolate (in other words, chocolate made with more than one variety of cocoa) can be delicious and sometimes more balanced than single-origin chocolate. On the opposite end, single-origin chocolate clumsily made with poor-quality beans won’t taste good.

However, as a general rule, if your chocolate is made with single-origin, fine-flavor beans, you’re looking at some carefully crafted chocolate. That’s because the maker has taken time to taste all the flavors in the beans and bring them out in interesting ways. What kinds of flavors? Beyond sweet, nutty, and roasted, think fruity, floral, earthy, dairy, and spicy. And on and on!

TEXT EXCERPTED FROM BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE © MEGAN GILLER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.