Ten Tips for Becoming an Observant Naturalist

To be a naturalist today is to find a balance between embracing modern technology and cultivating a direct and contemplative connection with nature.

This is an extraordinary time to be a naturalist. By naturalist, I simply mean someone who is attuned to and enthusiastic about the natural world. Never before could the average person pick up an unfamiliar insect, flower, or mushroom and, without even leaving the forest, immediately identify it and discover everything known about it by consulting a smartphone.

In real time, each of us can add to the world’s knowledge by pooling our observations online with those of thousands of other naturalists here and abroad. Citizen science websites such as eBird and iNaturalist can then instantaneously digest our observations, locate them on a global map with a time stamp, and feed them back to us. By sharing our observations with the public and with decision-makers, we can influence national and international environmental policy and help protect our natural heritage. Ordinary naturalists can gain an unprecedented understanding of the natural world thanks to the advent of breathtakingly detailed nature videos, remote sensing by satellites, scanning electron microscopy, webcams, drones, molecular techniques, and other tools.

Contemporary naturalists can and should embrace modern technology and the ability to be connected to knowledge and each other via the Internet, social media, and mobile devices. But we must also leave room in our lives for a genuine, direct, and contemplative connection with nature. The question is, how do you make that connection?

The answer is straightforward: by being present, mindful, watchful, and willing to do a little work.

Here are ten guidelines I have found essential for my own growth as a naturalist that anyone can use.

1. Cultivate curiosity.

Becoming a good naturalist is mostly a matter of being attentive. That’s a habit that you can develop, but it takes practice. Why not try to learn something about the natural world every time you take a walk outside? That may sound compulsive; I prefer to think of it as being mindful.

2. Learn the names and taxonomy of plants and animals around you.

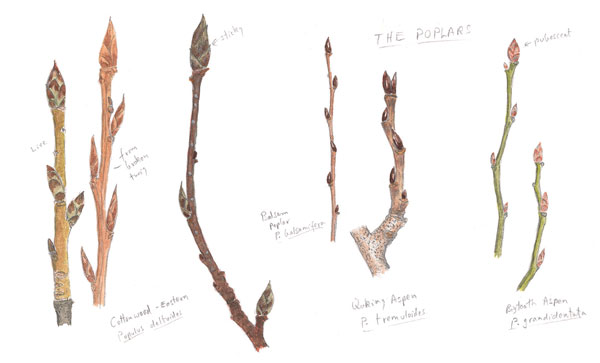

Conversations are much more interesting and useful when we all use the precise names of whatever we’re talking about. That is particularly true of natural history. Start with plants and animals that you encounter nearly every day. Though you may stick with common names, at least initially, you can learn a lot by glancing at scientific names. Recognizing general taxonomic categories — knowing families or orders, for example — can help you identify species and appreciate their evolutionary relationships with other organisms.

3. Become familiar with the basic ecology of plants and animals.

Learn as much as possible about what kind of habitat they prefer, when they breed, what they eat, who or what eats them, how long they live. The more natural history knowledge you acquire, the more you will see and learn.

4. Go on walks with knowledgeable naturalists, and take notes.

Take advantage of naturalist “teachers” whenever you get the chance. I learned most of what I know about nature by latching on to whoever was willing to download their extensive knowledge. If you don’t happen to know someone who can tutor you in the field, find out if there is a nature club in your area. Local Audubon societies, high school ecology programs, and museums are a resource for meeting wonderful teachers and naturalist companions. Consider taking or auditing a class at a college, university, or field station.

5. Ask “how?” and “why?” questions.

Once you can identify a plant or animal, don’t stop there. Cultivate curiosity with a purpose. Certainly you can look up on Wikipedia the answer to most questions you have about nature. But it’s more fulfilling if you follow Thoreau’s advice “to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it.” With time and the gradual accumulation of observations, you will be able to ask more complicated questions and anticipate when different events in nature will occur in the future.

6. Scrutinize, touch, smell, listen, measure.

Actual experiences lead to more enduring memories and a more profound comprehension of the natural world. If you know what you’re doing, and if you exercise moderation when engaging in a hands-on approach to learning about nature, you will learn more. Many experienced naturalists follow certain rules, or field ethics, that serve as good guidelines. They will not handle, dissect, uproot, hold in captivity, or kill anything if it causes undue suffering; if it diminishes somebody else’s experience (e.g., plucking the sole example of a beautiful flower alongside a popular trail) or is prohibited by law (e.g., collecting specimens in a state or national park); if it jeopardizes a species that is rare, threatened, or endangered.

7. Conduct simple experiments.

Experiments are not just for scientists. Anyone can snap a twig and come back a little later to see how quickly it drips sap and what it tastes like. Simple manipulations of nature like this permit you to peer into the minds of animals as well as gain insights about their physiology and behavior. If you want to understand the “how?” and “why?” of nature, try an experiment. The wonderful thing about the scientific method is that whenever you discover an “effect” of a manipulation, new questions arise.

8. Teach others.

One of the best ways to solidify what you know about nature is to share your knowledge with others. If you know something well enough to be able to explain it coherently, then you truly understand it. Anyone can be a teacher, and your children, siblings, parents, friends, and neighbors will very likely be grateful pupils.

9. Analyze your observations.

The longer you continue your observations, the more valuable your records will become. And the more you ponder the resulting patterns, the more profound will be your understanding of nature. Consider summarizing your observations in a table or timeline, highlighting the earliest, latest, and average dates of different natural history events, or use a graph to illustrate the long-term patterns you see in nature. Such an analysis of natural events that you have seen at one place over time can be a significant contribution to climate science.

10. Put knowledge into action.

We are in a time of unprecedented environmental challenges. Changing climates, deforestation, and urban sprawl are driving species to shift their geographical ranges and migratory routes. Even a casual observer can note how quickly invasive species like kudzu, bittersweet, or multiflora rose are spreading. If you make observations in a consistent manner over the course of only a few years, you can document the decline of species, such as little brown bats or monarch butterflies. And you can make your own contributions toward solving our environmental problems by reporting those transformations of our planet.

Excerpted from The Naturalist’s Notebook © By Nathaniel Thoreau Wheelwright And Bernd Heinrich.